The Donkeys of Midway Island

By Gary Randall

Author’s Preface

My interest in the story of the donkeys of Midway comes from

a personal place. I lived on Midway Atoll for two years while serving in the

United States Navy. Those small islands—Sand and Eastern—leave an imprint on

anyone who has known them: the ocean breeze, the unbroken horizon, the cry of

the seabirds. While I was stationed there, I sometimes heard mention of a

donkey that had once lived on Eastern Island, a story told with little detail

and no certainty.

Years later, I began searching for the truth behind that memory. What began as

a curiosity soon became something deeper. In the pages of old Honolulu

newspapers and in the recollections of men who had served there long before me,

I discovered not just a single donkey but an entire forgotten chapter of

Midway’s history—a story that reached from the earliest days of the cable

station in 1904 to the final years before the war.

As I traced the lives of Carrie, Dowie, and the little filly called Little

Carrie, I found myself moved by their endurance and by the strange tenderness

of their exile. The donkeys of Midway were never meant to be there, yet they

survived in that place of salt and wind for nearly forty years. In telling

their story, I found a connection not only to the islands where I once served

but to the quiet, persistent spirit of life itself—something humble, steadfast,

and enduring.

This work is, in a way, a return to that place. It is for the donkeys who once

brayed across the lagoon, and for everyone who has ever stood on Midway and

listened to the wind and wondered what stories it carries.

— Gary Randall

The Donkeys of Midway Island

By Gary Randall

The winds and ocean breezes never truly stop at Midway. They drift across the atoll and over the lagoon, carrying the cries of seabirds and the taste of salt on its breath. If you stand on the beach of Sand Island and look across the narrow stretch of turquoise water toward Eastern Island, you can almost imagine movement there—not the restless wheeling of albatross wings but something slower, quieter, and long vanished. The birds rule it now, but once this calm lagoon echoed with another kind of voice: the rough, plaintive bray of donkeys.

It was never their idea to come here. Their story began not in adventure but in practicality, with a man who struggled to walk in the island’s sand with his disability.

At the dawn of the twentieth century, the Commercial Pacific Cable Company undertook one of the great engineering feats of its age—an undersea telegraph line that would link the United States with the Philippines and the Far East. Midway Atoll, a lonely ring of coral more than a thousand miles from Honolulu, became the halfway station that kept the current of messages alive. By 1903, the company’s relay station stood on the larger of the two islets, Sand Island. A handful of men lived there—operators, engineers, and laborers—separated from the world for months at a time, surrounded by the unbroken wind and the unending sound of seabirds.

Among them was the station doctor, a man whose name has been lost to history but whose condition has not. He had a wooden leg. On firm ground he might have managed, but on Midway every step sank into the deep sand. What for others was an inconvenience was for him exhaustion. He was not one to complain, but at last he asked the captain of the company’s supply ship to bring him a small donkey from Honolulu—a sure-footed animal that could carry him where his wooden limb could not.

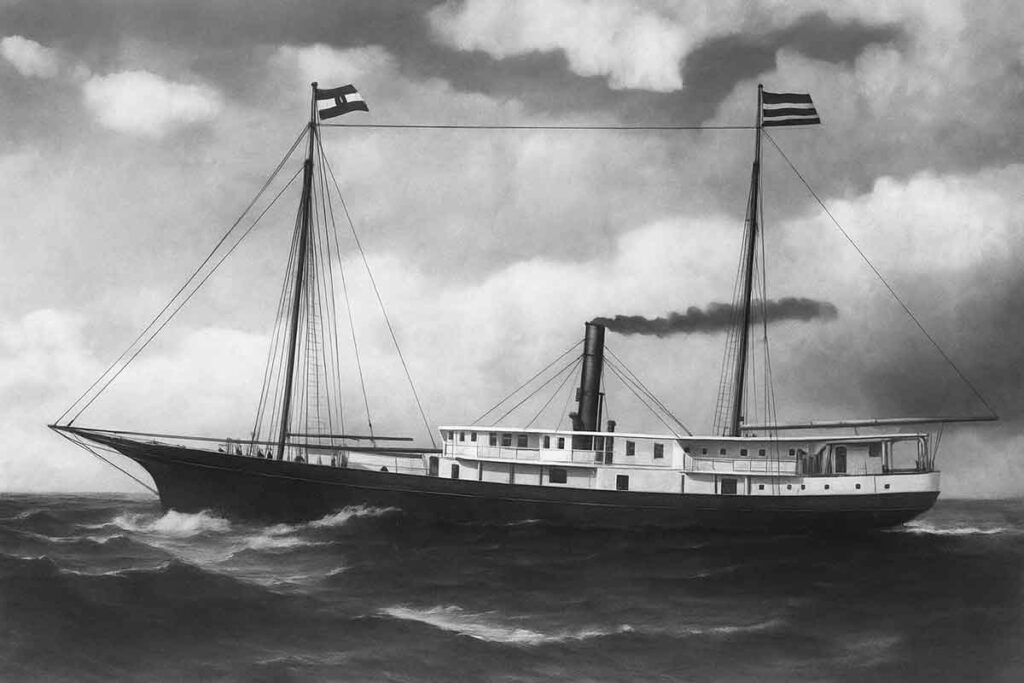

The captain, likely George Piltz, commanded the Iwalani, a sturdy steamer of the Inter-Island Steam Navigation Company. He took the request to heart. When the Iwalani steamed into Midway’s lagoon on December 19, 1904, she carried a cargo so unusual that the Hawaiian Star reported it with amusement: “The vessel resembled a circus boat,” the paper said, “laden with ducks, geese, turkeys, cows—and two donkeys.”

The doctor had asked for one. The captain, ever obliging, had brought two.

They were named Carrie and Dowie, in the ironic humor of the age—Carrie for Carrie Nation, the hatchet-wielding crusader against drink, and Dowie for John Dowie, a fiery evangelist and station minister from Illinois. No one could have guessed that these small, gray creatures would outlast nearly everyone who knew them. For the doctor they were a blessing. They carried him across the dunes and hauled small loads; they gave him back a measure of freedom. For the rest of the men they were a diversion, something alive and unpredictable in that wind-scoured place.

Before the doctor’s year was done, Carrie and Dowie produced a foal—the first born on Midway. By the time he sailed home, there were three donkeys on Sand Island. The novelty faded quickly. The animals ate what little grew in the station’s garden, trampled the vegetable beds, and gnawed at wooden posts. Feed shipped from Honolulu was costly. Once useful, they became pests.

Across the lagoon lay Eastern Island, smaller, greener, and uninhabited, its low flats covered with thick scaevola shrubs and patches of purslane. It seemed the perfect place for banishment. Sometime around 1905, the three donkeys—Carrie, Dowie, and their nameless foal—were ferried across the lagoon and turned loose. The men went back to their duties; the sound of braying became only another note in the Midway wind.

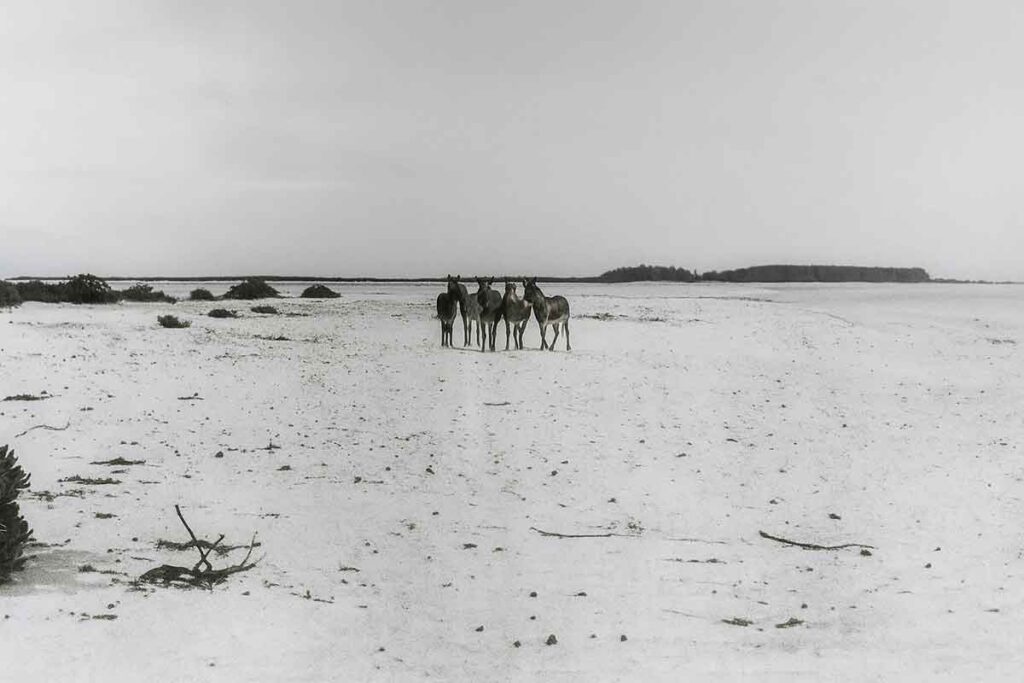

On Eastern Island the animals adapted. They learned to live on the coarse leaves of the shrubs and to dig for water in the sand, following the faint scent of dampness. They endured the heat and the salt and the long, dry months when rain did not come. In time their numbers grew. By the early 1920s, roughly two dozen donkeys wandered the island, their coats bleached by the sun, their manes tangled with salt. From Sand Island, men could sometimes see them moving in the haze or hear their brays drift across the lagoon. They called them the Eastern Island Nightingales.

In 1923 the U.S. Navy’s minesweeper Tanager visited Midway on a scientific expedition. Its restless sailors, eager for sport, crossed to Eastern Island and gave chase to the wild herd. They captured five donkeys, and one small specimen was carried back to Honolulu as a curiosity. A newspaper noted dryly that “the ancestors of this representative were taken over to Midway when the American cable station was young. They have thrived, but are wild.”

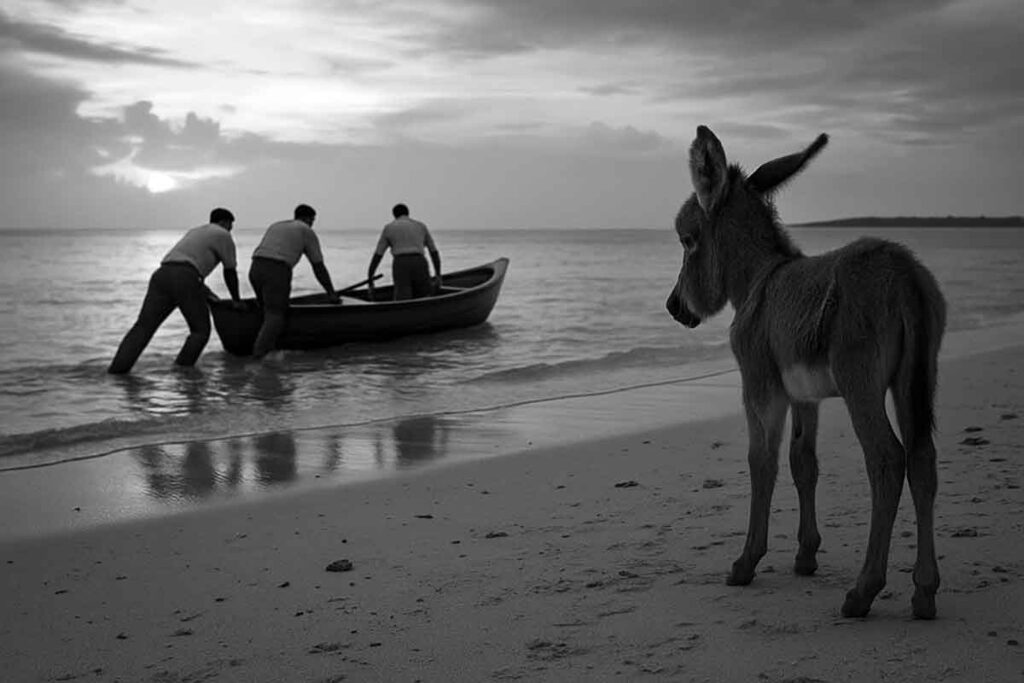

So they were—wild and thriving still when Dr. Donald R. Chisholm arrived at Midway in the late 1920s as the station’s medical officer. The stories of the Nightingales intrigued him. One bright morning he and two cablemen paddled a canoe across the lagoon to see the animals for themselves.

They landed on a beach littered with coral fragments and feathers. Not far inland they found a small group of donkeys grazing among the scaevola. One was a filly, slender and curious, trailing her mother. They caught her easily; she was too young to fear them. The men laughed and fed her bits of sugar and sandwiches from their pack. She ate delicately, licking the peanut butter from the bread, and when they decided she needed a name they called her Little Carrie, in honor of the original matriarch whose tale had long been legend on the island.

For the rest of the day she followed them like a shadow, trotting behind through the sand, her hooves leaving small prints beside their own. When they walked back to the canoe at dusk, she came too. Her mother stood at a distance, watching but untroubled.

The men hesitated at the water’s edge. They could not take her. She belonged to this desolate place, and to remove her would only condemn her later. They fed her the last of the sandwiches and poured a quart of water into a pan for her. When they pushed off, she tried to follow. She waded out until the water reached her chest and tried to climb into the canoe, braying softly. They pulled her clear of the lagoon and set her back on the beach. As they drifted away she cried out again—a sound that Chisholm remembered as “the sobbing dissonance of a disillusioned child.” Twice she waded in, twice they rescued her. The third time they left her standing on the shore, the light fading behind her.

Her cries followed them across the lagoon until the sound was lost in the surf. Chisholm never saw her again.

Through the 1930s the herd lingered on, smaller now, half-forgotten. The donkeys grew lean, their coats rough and scarred. Yet still they survived—digging their wells, browsing the native vegetation, standing motionless in the sun while clouds of seabirds wheeled overhead.

When the Navy began to fortify Midway before the Second World War, the atoll changed forever. Runways were laid, barracks built, and bulldozers roared where the donkeys had grazed. By 1941 only two remained. One, according to longtime resident Ed Hansen, was a jenny named Carrie. Whether she was the same Little Carrie who had followed Chisholm’s canoe or a descendant bearing her name, no one could say. That year the last pair were shot, and the Eastern Island Nightingales were gone.

A decade later, Dr. Chisholm—by then far from Midway—set down his memories in an article he titled Those Donkeys of Midway. It was published in the Honolulu Star-Bulletin in May 1955. His words were tender and unpretentious. He wrote of the donkeys’ endurance, their patience, their quiet suffering. “They endured the bitterness of exile,” he said, “with a fortitude that might shame our own.”

Former cablemen who read his piece wrote to the paper, recalling the doctor with the wooden leg, the little steamer Iwalani, and the sight of the animals standing on Eastern Island at sunset, watching the sea. Each remembered the sound of braying across the lagoon, a memory half humorous, half heartbreaking.

Today there are no donkeys at Midway, only the birds and the wind. Yet on calm days, when the lagoon lies glassy under the sun, one can imagine a faint echo—a thin, uncertain note drifting across the water, as if the Eastern Island Nightingales were not entirely lost to time.

Historical Note and Acknowledgments

The story of the donkeys of Midway Island was pieced together from early twentieth-century newspaper accounts, official reports of the Commercial Pacific Cable Company, and the recollections of those who lived and worked on the atoll during its earliest years. It draws on publications including The Hawaiian Star (1904), the Honolulu Star-Bulletin (1919–1955), and the Honolulu Advertiser, among others. Particular gratitude is due to Dr. Donald R. Chisholm, whose 1955 essay ‘Those Donkeys of Midway’ preserved the heart of this story for future generations.

Note: Some of the images included in this article are reproduced or are repaired versions of actual photographs from contemporary newspapers using ChatGPT.